In Search of the Elusive International Institutional Investor

Considering all the woes that are afflicting developing market countries today, be it climate change, mass migration, fiscal imbalances, and yes, COVID-19, it should come as no surprise that development finance organizations collectively lack the necessary capital to attend to all those needs. What about institutional investors?

Institutional investors typically include asset managers, insurance companies, pension funds, sovereign wealth funds, foundations, endowments, family offices, etc. They have many common characteristics, but their investment strategies can be very different. For example, investors with specific of guarantees on capital or returns have to implement investment policies in compliance with their outstanding liability. Meanwhile, asset managers, sovereign wealth funds, family office or foundations, can base their investment policies merely on optimal allocation of assets, albeit minding the needs of liquidity requirement or other specific mandates.

Financial regulation is another key driver for investment policies. Commercial banks and insurance companies are subject to stringent regulatory constraints on their capital adequacy and risk exposures. For banks, it’s a complex combination of international standards such as Basel Accord and domestic regulations. As for insurers, it’s the solvency requirement. By comparison, asset managers, family offices and other investment funds are often facing less stringent regulatory constraints but have to adhere to their asset allocation mandates.

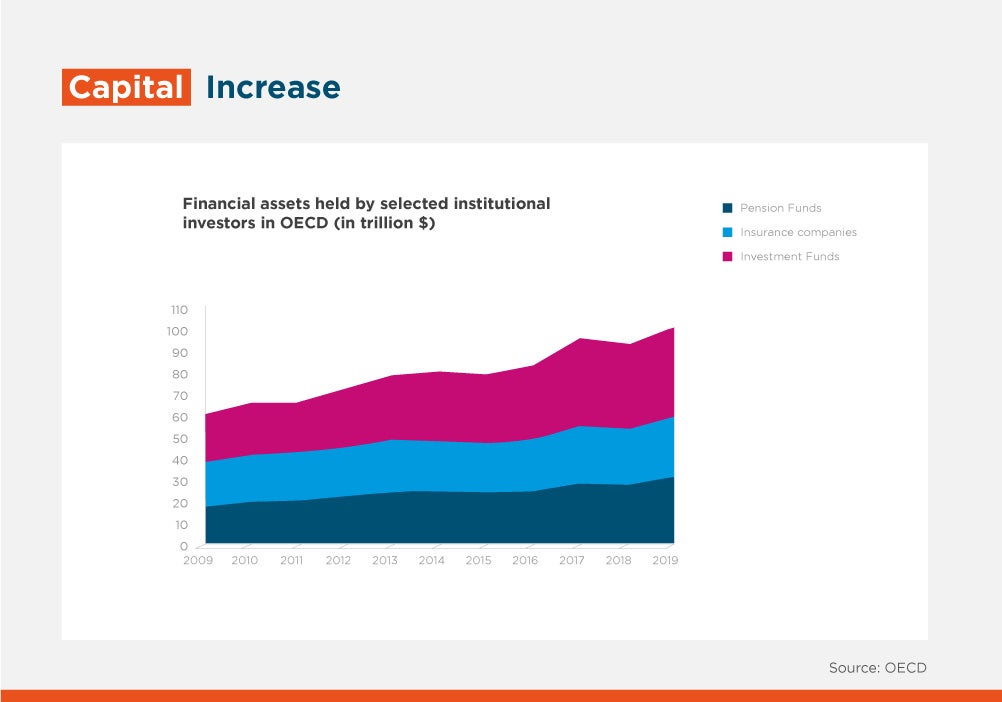

Assets under management (AUM) across the institutional investor space have soared over the past decade, but very little of that money flowed to Emerging Markets (EM), and even less so to those countries that are non-investment grade (non-IG). The aggregated amount of financial assets held by pension, insurance company and investment funds in OECD economies exceeded 100 trillion dollars in 2019 and keep rising.

That amount as percentage of GDP has increased too, with at least 16 countries having levels exceeding 100%. However, capital flows to EM and non-IG debts are very limited. For insurance companies, in European countries, only 3-4% of insurer capital goes to EM assets and about 1-2% of total bond exposure is to non-IG issuers, according to the European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority. Likewise in US, less than 1% of insurer assets is allocated to EM and about 10% of insurance industry’s EM bond exposure is on non-IG securities.

In terms of asset managers, they are strategy driven. Their portfolios concentrate heavily on investment grade debt and liquid assets. Only 15% of total invested capital is allocated to EM assets and other high-yield or illiquid debt. When it comes to family offices, the situation is similar. Only 12% of their portfolio is in EM assets, split evenly between equity and fixed income.

Financial regulation is the main structural constraint for institutional investors to scale investment in EM. The higher the risk of a particular investment, the greater the amount of capital that an institution must keep in its balance sheet.

Under the newly proposed NAIC guidance, aimed at providing more granularity in the ratings, investing in non-investment grade assets remains quite punitive: US Insurers capital requirements increase 5.1x when investing in single-B (the median rating for EM) vs BBB assets. In the EU, insurers are governed by Solvency II. The capital requirements of EU insurers increase 2.8x when investing in single-B and below, vs BBB assets.

For commercial banks, under the standardized approach, Basel III requires a 100% capital risk weighting for “BB+ to BB-” and 150% for “below BB-” credits, while it’s only 75% for “BBB+ to BBB-” under the Basel III Capital Requirements. However, most international banks follow the advanced approach, which relies on their internal model, investing in EM or non-IG debt induces significant “capital” cost for those institutional investors subject to financial regulations.

Other barriers for institutional investors include unfavourable or uncertain regulations and policies, tariffs, collateral and security, a lack of bankable projects and even risks of political and macroeconomic instability. Other challenges are the lack of viable funding models and inadequate risk-adjusted returns, inflation or foreign exchange risks, illiquid capital markets, and a lack of data.

Emerging Markets offer limited investment grade opportunities. Of 156 emerging markets countries, the overwhelming majority (83%) are rated below investment grade or unrated and 43% are currently in selective defaults or unrated. Among those rated, median sovereign rating is only single-B. Moreover, even if some EM countries do have access to institutional investors’ capital, most of them are countries not in the list of recipients of Official Development Assistance, or ODA. When we look at the ODA-eligible countries, investment grade bond supply is even scarcer. 91% of ODA countries have non-IG rating. Half of ODA countries are unrated or selective defaults.

To unlock at least part of the $100 trillion in assets under management for the benefit of EM, we need to acknowledge that, barring any drastic changes in regulation or evolution in emerging economies credit worthiness, the permanent and long-term structural fix is supporting countries’ economic growth and fiscal resiliency through traditional development assistance levers.

In the meantime, we can use blended finance as a de-risking tool, but with a demand-driven approach. The ability to fully leverage blended finance is indeed often constrained by a sectorial and geographical focus due to donors’ heterogeneous requirements. For instance, blended finance resources are generally limited to a subset of financial instruments, specific themes or select geographies. Widening the thematic and geographical scope of those resources is paramount to support mobilization efforts, especially in portfolio approaches where diversification is a must.

Furthermore, blended finance instruments which main objective is de-risking should avoid subsidizing institutional investors. Risk profile is the binding constraints, not the underlying projects’ profitability. Since regulation and country rating ceiling constraints are there to stay in the near future, scaling de-risking blended finance instrument can only be achieved on the back of low – or ideally even negative – ODA. Thus, public money can be used in a single project or an aggregation vehicle to allow for an investment-grade tranche that will cater to institutional investors. All else been equal, that public money should receive a remuneration commensurate with the risk it is taking, taking advantage of the fact it is not restricted by solvency regulations. Subsidies, if any, should be used in very specific cases.

Donors should consider channelling blended finance resources to entities with both on-the-ground execution know-how, distribution expertise, and “honest-broker” capabilities to ensure an adequate alignment of interest between the different parties. Multilateral development banks have a unique set of competitive advantage to play that role, thanks to their execution and syndication capabilities, dedicated blended finance governance and impact measurement frameworks.

LIKE WHAT YOU JUST READ?

Subscribe to our mailing list to stay informed on the latest IDB Invest news, blog posts, upcoming events, and to learn more about specific areas of interest.

Subscribe