A Return to Office without Returning to Same Old Discrimination Patterns

There’s a little-noticed issue within the larger debate on the mass return to office as pandemic measures abate. But it’s a very important issue for minorities.

Across Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC), as well as in the global West, the corporate world entrenched in office spaces is mostly White. It’s hard to compile regional-wide statistics but, in the U.S. for example, whites are far likelier to hold managerial positions than Black and Latin employees, according to estimates by the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

At the top of these hierarchies, 93% of the CEOs in the Fortune 500 are White, while two-thirds of the C-suite executives are White men in particular.

These numbers are cited in a fascinating little piece in the Harvard Business Review, as support for a very important point: that minorities in the U.S. – and arguably elsewhere – were to some extent made invisible by working from home during the pandemic, and this helped them combat discrimination as it focused discussions about job performance on measurable merits, rather than intangibles that are often used as code to maintain power imbalances.

A key point here is the often exaggerated importance of face-to-face meetings. Multiple high-profile American companies rushed to force employees into their offices as soon as it was humanly possible, even as the pandemic still raged, arguing that the type of work they do requires present, physical contact with clients and co-workers.

This is sometimes easier to justify, for example when you have a company in the manufacturing sector; but it’s harder when you have a company that has a number of employees meeting clients but also many others in back-offices or staring at computers or trading terminals all day.

You may have heard of the oft-quoted expression Great Resignation, referring to all the employees who have voluntarily resigned en masse from their companies – often just at the point when they were forced to return to the office, after having teleworked during the pandemic.

This trend may be particularly acute among minority workers, as they return to office to find unchanged work patterns, unclear informal mechanisms to evaluate performance, company events at which they may not wish to participate and that may be culturally insensitive as they typically cater to the dominant, majority culture.

HBR cites data from Future Forum showing that the telework revolution coincided with significant increases in U.S. Black knowledge workers employee experience scores. Compared with May 2021, Black employees are now reporting greater “sense of belonging” at work (up 24%), higher “value of relationships with coworkers” (up 17%), and a stronger perception of “feeling fairly treated” (up 21%). What these people say is that, by spending less time in the physical office, they have to engage less in “code switching”: changing one’s behavior, appearance, or speech to fit into the dominant culture.

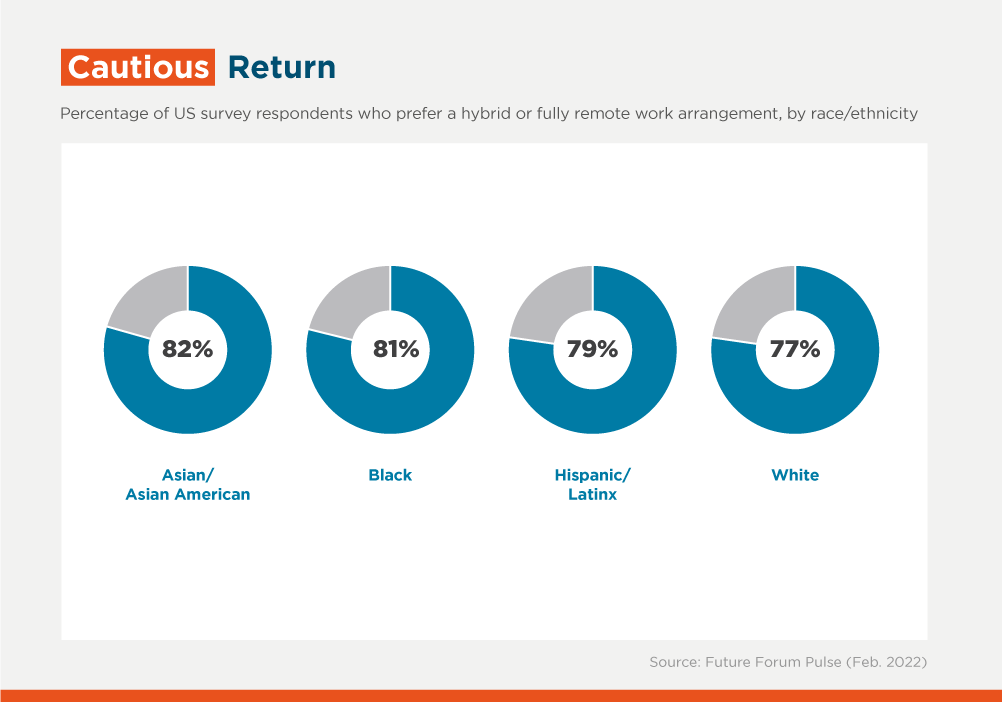

Since telework removes extra emotional labor, it’s easy to see why 81% of U.S. Black knowledge workers say that they prefer a hybrid blend of in-office and remote work going forward. The same logic applies to women and other under-represented groups. And Future Forum data shows that 60% of Black employees who are not happy with the amount of flexibility they have at their current jobs will look for a new one in the coming year – thus joining the Great Resignation.

Companies must pay attention to this data. Diversity initiatives must go beyond nice words and take the experiences of minority employees into account. Flexibility is required, and also more clarity when it comes to performance assessments in the new post-pandemic world.

LIKE WHAT YOU JUST READ?

Subscribe to our mailing list to stay informed on the latest IDB Invest news, blog posts, upcoming events, and to learn more about specific areas of interest.

Subscribe